By Lane Florsheim

The artist's new show 'Linescape' opens October 2 at Acquavella Gallery in New York.

Jacob El Hanani's studio is immaculate. The hardwood floors gleam and neat rows of books are stacked along shelves against walls near the entrance. During my visit, he takes out various binders, exhibition catalogs and drawings before returning each to its exact place in a filing cabinet or drawer below one of the two tables where he draws. "It's always like this," he says.

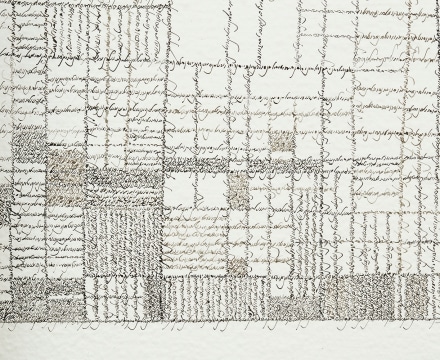

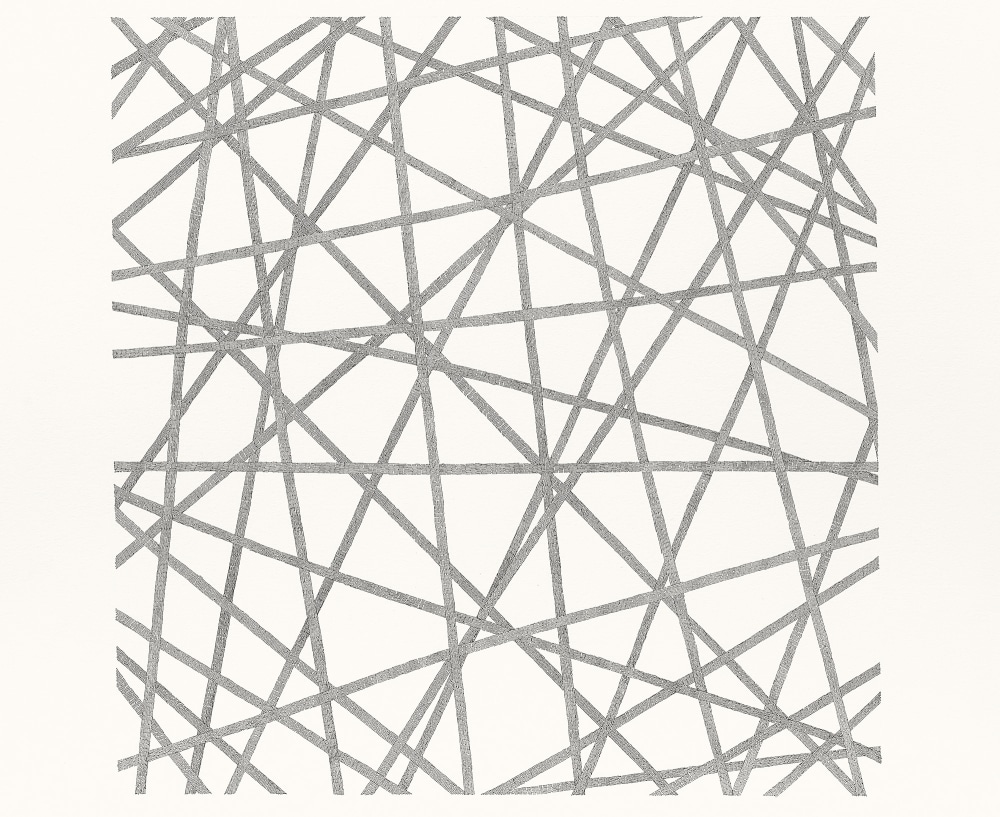

In the context of his work, El Hanani's neatness coheres. From a distance, his pieces look abstract: a hazy gray square on canvas, a roiling atmospheric formation, a collection of intersecting lines. But standing closer one notices that each shape is in turn composed of thousands of tiny lines, made with a quill or a Rapidograph techinical pen. Sometimes El Hanani, who has been called the grandfater of micro-drawing, draws miniscule characters from the Hebrew alphabet, referencing the Judaic tradition of micrography. "Usually, I don't get the 'Wow.' I get the, 'How?'" he explains as I inspect one. It would be easy enough to pass a drawing of his by without noticing the innumerable marks -- they unfold to the viewer like a secret.

For decades, El Hanani has been driven by the desire to bring drawing to this extreme in an attempt to break the notion that miniature is a small-scale work. "When I moved to New York in the '70s, everything was, My car is bigger than your car and my apartment is bigger than your apartment," he says. "Now it's, My cell phone is smaller than yours. My gadget is smaller than yours. So, the miniaturization of the planet..." he considers. "Well, the Japanese already started that 400 years ago."

The number of hours it takes to achieve the precision found in every centimeter of his work defies today's ethos of efficiency and reverence of technology. Younger viewers, he says, often don't believe the pieces are by hand, or done without the help of an assistant. Later, he mentions he hasn't accomplished all he wants to do, like spending a whole year, uninterrupted, on only one piece. Even though some of his works have taken years, he is always working on a number of drawings.

El Hanani's new show Linescape opens October 2 at Acquavella Galleries in New York and covers nearly forty years of his practice. "I would call myself a line-maker," he says of the show title. "When people say to me, 'What do you do for a living?' I say, 'I make lines' ... Is a line-maker something in football?" he adds, seeming sincere. He categorizes his earlier work as more austere, in keeping with minimalism's de rigeur opposition to figuration in the '70s. He sees his recent pieces, some of which reference Piet Mondrian's grid paintings and J.M.W. Turner's vivid landscapes, as freer.

El Hanani was born in Casablanca and moved to Israel when he was seven, where he was "the artist of the kids," copying the drawings of Albrecht Dürer and Giorgio Morandi. He spent two years at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris in his twenties before moving to New York City "for the space." A tthe time, he explains, artists could only get 200 or 300 square feet in Paris for the price of 3,000 in New York. Once in New York City, he eliminated every trace of figuration from his work in 1972 and found his new process demanded 12 hours a day. He worked constantly. "I was able to survive without having a day job. If I sold a drawing, I paid my rent. That generation was really supportive of artist and art."

El Hanani's work develops organically, without subjects in mind, but sometimes he finds personal or historical meaning in a piece after it is complete. He once made a series of drawings that turned out to be gauze fabric and then learned that Gaza is thought to be the origin of gauze. "Gaza was important to me because when I was in the Israeli army, we occupied the West Bank. I've been twice in Gaza," he says. "Unconsciously, I figure, I ended up drawing gauze."

During my visit, El Hanani also shows me the darwings he doesn't exhibit: the sheets he fills with figurative doodles (eight favorites are framed and displayed on the wall) and a binder of his cartoons, explaining that, like Michael Jordan playing golf to unwind, artists relax by making different kinds of art. "My case was being a paparazzi cartoonist quietly in a cocktail when nobody could see me," he says. He shows me the likenesses of Norman Mailer, Henry Kissinger and a young Donald Trump along with many others.

When he opens the drawer to one of his cabinets, revealing a charcoal sketch of a nude model sitting on her knees, he says quickly, "It's not important. Hundreds of artists do that in art school." But then he adds: "However, sixty years from now, my son will be 74. And I'm dead, and if someone says, 'Oh you have a drawing of your father's from 100 years ago?' Suddenly it becomes important for a collector."

"All that we can do is leave the pile slightly higher than what it was. I'll be known for making little, tiny lines," he says. "Period. You cannot achieve a lot in art. You have to make your own contribution."